Crabbers pull up gear as hurricane ends season

Published 6:23 pm Friday, October 21, 2016

Hurricane Matthew put an official end to the commercial crabbing season on the Pamlico River.

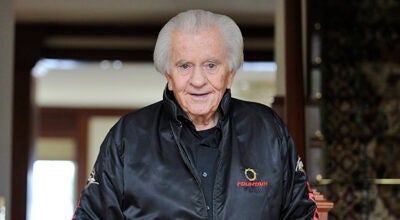

On Friday, crabber Tommy Franz pulled 74 of his crabpots from the river; the remaining 150, he’ll retrieve on Monday. In a region where the commercial season can last well into November — and sometimes December — the torrential rains unleased by the Oct. 8 hurricane, and the resulting floodwaters still making their way down to estuary, brought the season to an abrupt halt.

“We would have kept on crabbing, and most of the others would too. Everything’s directly related to the hurricane, though there wasn’t substantial damage,” Franz said. “We’re the last ones to quit. Most everyone else pulled up prior to the hurricane and then realized there was no reason to put it back.”

Franz said he’d seen this situation before: in 1999, after Hurricane Floyd. The similarities exist, from the devastation of Princeville up the Tar River, to the abundance of freshwater moving quickly, pushing debris and prompting some aquatic species to go with the flow of their more natural habitats of brackish water.

Hurricane Matthew will continue to have impacts on eastern North Carolina for some time to come, according to officials. Thursday, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality issued a press release warning people in to avoid contact with waters of the Neuse, Pamlico and Cape Fear rivers.

“Floodwaters often contain pollutants, such as waste from septic systems, sewer line breaks, pet and wildlife feces, petroleum products, and other chemicals,” the press release reads. “Those who come into contact with these waters have an increased risk of contamination and adverse health effects, such as diarrhea, abdominal cramps and skin infections.”

During Hurricane Matthew and the days of upstream flooding after, DEQ’s Division of Water Resources received several reports of untreated wastewater entering the waterways: in Princeville, Tarboro, Greenville and Washington. In Washington, approximately 1 million gallons of wastewater were discharged in Jack’s Creek, due to a two-day power outage, a malfunctioning backup generator and a bypass pump unable to keep up with the sheer amount of water in the sanitary sewer system. Greenville’s was much smaller, at approximately 15,000 gallons. It is unknown how much wastewater entered the Tar River in Princeville and Tarboro, as those facilities were underwater, according to officials.

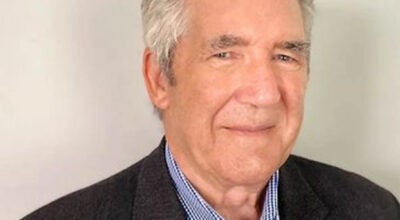

Ben Peierls, a research associate with University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences, said one of the possible effects of such discharges into the waterways, is they could have a fertilizer effect: nutrients — primarily nitrogen and phosphorous — in the discharge may promote the proliferation of cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, which was an ongoing problem in the Pamlico and its tributaries over the summer.

“The water has freshened dramatically from what conditions normally are. It’s fairly turbid water — it’s cloudy and filled with particles, and oxygen levels are lower than what they normally should be,” Peierls said.

Peierls said the amount of water making its way down the river systems is so massive, and moving so quickly, it’s pushing brackish waters normally found inland into the sounds, and even into the ocean. This a repeat of Hurricane Floyd, which in 1999 led to a massive blue crab migration out of the rivers.

In the coming weeks, fish kills could be an issue due to low oxygen levels and potential explosion of cyanobacteria. However, the sheer amount of water flowing in the rivers could dilute nutrients enough that no such thing occurs, Peierls said.

“We don’t know what will happen. We’re right in the middle of it, so it remains to be seen,” Peierls said. “A lot of the impacts of this event depend on the rainfall, precipitation patterns, of the next few weeks. … If there is more rain, it’s just going to add to it.”

What the conditions represent to researchers is an opportunity to study those exact effects in the amplified environment of flooding on a massive scale.

“Water takes a fairly long time, weeks months, to move through the (estuarine) system. When you get an event like this, it’s moving much more quickly through,” Peierls said. “This is the perfect opportunity to get some really interesting data.”

That data is used to inform government assessments on the health of the state’s estuarine systems.

For now, the only official outcome is that blue crab season for commercial crabbers is over. Farther downstream, there could be problems to come over the winter months, according to Franz.

“I think there’s also another issue and that’s the oysters. I think it’s really going to hurt those boys,” Franz said.