Legislation poses negative impact for Pamlico-Tar rivers

Published 12:15 am Sunday, June 28, 2015

EPA

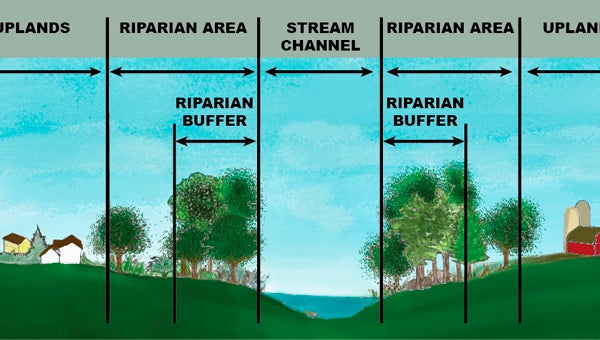

HOW BUFFERS WORK: The hardwoods and larger vegetation planted along any waterway work to remove nutrients before pollution gets into the waterways. Legislation being considered in the N.C. General Assembly makes drastic changes to what is and is not considered a buffer.

New legislation could have a long-lasting impact on the quality of local waters.

House Bill 44, now waiting to be decided by a special committee of members from both the N.C. House and Senate, will potentially remove the means by which the estuary self-cleans: riparian buffers, the area of hardwoods, shrubs and native grasses that remove pollution from the waterways.

The bill reduces buffers from the current 50 feet to 30 feet and would allow landowners to clear-cut down to the water’s edge as long as any vegetation removed is replaced. However, the bill does not specify what the removed vegetation should be replaced with. Since the key part of nutrient removal is done by trees, particularly hardwoods, by removing those, any pollution protection is also removed, according to Pamlico-Tar Riverkeeper Heather Jacobs Deck.

“Basically, it’s saying we’re going to get rid of the 50-foot buffers,” Deck said.

Deck explained the buffers were put there for a reason: in the 1990s, the federal government stepped in and told North Carolina to clean up its act, in keeping with the Clean Water Act. The intervention was prompted by a large number of fish kills, including one in 1995 that lasted three months and killed tens of millions of fish. A group of stakeholders met — scientists, representatives from local governments, state regulators, developers, farmers, landowners and environmentalists were all invited to participate and together came up with water-quality management rules for Pamlico-Tar rivers, the Goose Creek watershed, Neuse River, Catawba River, and the Jordan Lake and Randleman Lake watersheds. The rules: 50 feet of vegetative buffer, the first 30 feet back from the water (Zone 1) must remain undisturbed; Zone 2, consisting of the next 20 feet, can be graded and replanted. A natural filter was a practical solution to reducing nutrient runoff into streams, creeks and ultimately rivers, Deck said.

“Letting trees and natural vegetation do the work is the cheapest thing you can do,” Deck said.

The legislation being considered could cost landowners, fishermen and taxpayers money in the long run.

For landowners, the same vegetation that acts as a filter also acts as an anchor, holding down land on the banks of water bodies. If property owners do away with their buffers, erosion could be a real threat there and on neighboring properties. The solution is expensive bulkheading.

West of Washington, drinking water for most municipalities along the Tar River comes straight from the river. The more pollution there is, the harder it is to treat the water.

“Compromising buffers shifts the burden of cleanup to taxpayers who will bear the increased cost of upgrading expensive water treatment infrastructure,” wrote Harrison Marks, executive director of Sound Rivers, the joint environmental advocacy group of the Neuse River and Pamlico-Tar River foundations.

And should the federal government have to step in to enforce the Clean Water Act again, municipalities and agriculture entities may just end up paying a price with more costly pollution controls, Deck said.

“People who have permits to release nutrients — they’re going to be on the hook for this,” Deck said.

There are those who don’t believe the making the dramatic changers to buffer mitigation will do any harm. Senator Bill Cook (R-Beaufort) is an advocate for the change.

“This change will not affect the water quality as there is still a buffer in place with the saltwater wetlands or marsh areas. All we are doing is eliminating the double buffer that the old rules created. We are removing the duplication of protection, which provides no real additional environmental protection.

“We don’t want to penalize the use of property owners (in) upland areas when there is plenty of marsh to take care of the runoff. … This proposed change won’t affect one thing in the areas that don’t have sufficient marsh for a buffer, they will still have the full 50-foot buffer. In addition, there still will be a 30-foot buffer as well,” Cook wrote in an emailed response to one constituent asking the Senator to protect water quality in the area.

“(With this legislation) there is no remaining buffer, nor was there ever a ‘double buffer.’ Wetlands are defined in federal law as waters. You shouldn’t ever use your wetlands as treatment systems,” Deck said, adding that those areas are instrumental in the breeding and hatching of many species that fuel commercial fishery in North Carolina — compromising that means compromising an industry.

Deck said Cook’s response is based on a report that is not comparable to what the legislation proposes. The report cited was a N.C. State University study in which researchers added a pine buffer upslope from an already existing 60-foot to 100-foot hardwood buffer. The hardwood was doing the job — the additional pine buffer proved to be redundant, Deck said.

The bill will not go back to either chamber for a vote: the House passed H.R. 44 with one set of regulations, which the Senate loosened drastically. The House voted against the Senate changes, so a conference committee will have to find a compromise that will be sent to the governor’s desk to be signed into law.

“I would hope the legislators would think about the consequences of this,” Deck said.

If legislation is passed that essentially removes buffers from already nutrient-sensitive waters, Sound Rivers will likely be taking the case to the EPA.

“It rises to the level, for us, that we’re going to have to respond in some way,” Deck said.