The James Adams Floating Theatre: Part 2

Published 10:26 pm Friday, May 18, 2018

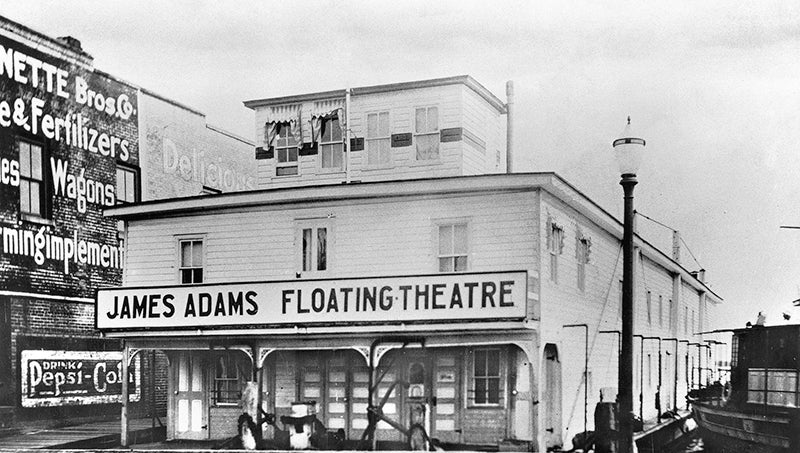

The original Show Boat of the Southeast, James Adams Floating Theatre, brought excitement and entertainment to coastal North Carolina and beyond in the early 20th century. Adams’ career and the fortunes of his floating theater were tied to changing tastes in popular entertainment and evolving technology.

How did he develop his “brainchild” which he had built in Washington, North Carolina? Adams was familiar with show boats on the Mississippi River, having been raised in the Midwest, and he was a vaudeville performer as a young man. Repertory theater was born in the beginning of the 20th century when a syndicate in New York controlled both the talent and the theaters, motivating lesser-known troupes of actors to begin travelling the countryside, bringing a repertoire to different places instead of remaining in one playhouse. Adams saved the cost of the venue by bringing his theater and performers to the people by boat, in a time when docking was cheap and shipyards readily available.

Adams’ entertainment formula on his floating theater combined plays in the popular forms of melodrama, comedy and tragi-comic drama. He encouraged audience participation with sing-a-longs and gags. Adams felt his best plays gave the audience a good laugh but also made them shed a tear. He also inserted his vaudevillian “bits and specialties” between acts of the plays. After the plays, one could buy a separate ticket for a late night musical performance.

This was not a time when audiences appreciated subtlety. Melodramas were action-driven and featured spectacular action with special effects; there was no character development, only “stock” roles such as heroine and villain. Virtue was always rewarded at the end, usually with a windfall or inheritance because this was also the era of enthusiastic materialism. Adams personally performed a “bit” which involved passing electricity through his body until the paper in his hand caught fire. He advertised that a man could feel comfortable bringing his wife and children to the floating theater. One of the standard comic “bits” from vaudeville, that Adams included, was a routine involving a white actor in “black face” — a white, stereotyped version of a black man. The character was a country bumpkin and the butt of the joke, but occasionally the bumpkin had the last word. The ingénue character was played through 1937 by Beulah Adams Hunter, Adams’ sister.

To illustrate changing audience tastes, in contrast to the stock characters and action-driven popular entertainment of earlier years, Edna Ferber included social issues in her 1926 novel “Show Boat.” One character in her story was Magnolia, who loved a gambling man. A subplot dealt with the problems of characters Julie and Steve, who were married and harbored a secret: Julie was bi-racial and “passing for white” at a time when marriage between the races was punishable by law. In this period, live entertainment was more popular than movies. In 1924, when Cecil B. DeMille’s first version of “The Ten Commandments” premiered, it was a silent movie.

In 1925, when Edna Ferber encountered the James Adams Floating Theatre while doing research for her book, Adams had ceased day-to-day involvement but retained ownership and the last word in all matters. In his place, the onboard manager was Charlie Hunter, Adams’ son-in-law married to Beulah. Both Beulah and Charlie charmed Ferber, and Charlie Hunter later maintained a correspondence with her. Adams eventually sold the boat in 1933. The new owner changed its name changed to the “Original Floating Theatre,” added a sexy chorus-line act, and directed the boat more often to the Maryland area and to some larger city ports. Its travelling range also expanded from Baltimore to Georgia, and audiences began to view the theater boat for its nostalgia value. Repertory theater declined when motion pictures became widely available and tickets very cheap.

The show must go on and, aside from numerous mishaps, the boat continued into the 1930s. In November 1927, it foundered off Thimble Shoals, Virginia, and was towed to Norfolk. In November 1929, after a stop in Cambridge, Maryland, it sank in the Dismal Swamp and was towed to Elizabeth City. In August 1933, a hurricane hit while it was docked in Cricket Hill, Virginia. Then in November 1938, after a stop in Colerain, North Carolina, the boat struck a log in the Roanoke River and sank again, only to be repaired and go on.

The “Original Floating Theatre’s” very last show played in January 1941 in Thunderbolt, Georgia, where the boat was sold for the last time. The new owner reportedly planned to convert it to a barge and wanted its tugboats, due to increasing demand for shipping. However, on November 14, 1941, less than a month before Pearl Harbor, the aging theater boat caught fire while being towed toward a slip in Savannah. When the tide went out, the boat burnt completely — literally going out in a blaze of glory. Thus, the “Original Floating Theatre” passed into history.

Billie-Jean E. Mallison is a member of the Historic Port of Washington Project, Inc; find us at www.hpow.org or on Facebook at HistoricPortofWashingtonMuseum. The Historic Port of Washington Project is seeking a home for its museum.