The Story of Keysville

Published 9:40 am Monday, February 13, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Clark Curtis

For the Washington Daily News

Editors Note: In recognition of Black History Month, with the assistance of Leesa Jones, director of the Washington Waterfront Underground Railroad Museum, Clark Curtis will take a closer look at some of the people, places, and events that have helped mold the story of Washington. The stories being shared are all part of Jones’ African American Walking History Tour of Washington. Black history is one of the cornerstones of the towns’ deep and rich history.

In 1837, Southby Keys a Black caulker in the shipbuilding industry by trade, purchased a huge portion of land from William Orr on the northeast side of Washington. The area was named Keysville. The purchase made Keys one of only 21 Black farmers who owned their own land in Beaufort County prior to the Civil War.

Keysville went on to be the most prominent and prosperous community in Washington. It was home to brick masons, plasterers, ship builders, caulkers, carpenters, farmers, tanners who made shoes and leather goods, and educators. All of whom were free and had never been enslaved. They had the freedom to work in Washington with no restrictions. And they would all play a significant role in the lives of Freedom Seekers. “Keysville would become known as “The Shadow of Egypt” in the Black community,” said Jones. “The word shadow in Hebrew was an emblem of protection. Egypt was a metaphor of bondage and slavery. Keysville would become a huge stop along the Underground Railroad as it was considered the shadow by Freedom Seekers, with Washington known as Egypt because of all of its’ slave trade and slave markets.”

Jones herself has deep roots in Keysville. A distant cousin, William Turner Harrison, owned a small home on Keysville road that still stands today. She vividly recalls many a day as a young girl sitting on the front porch listening to the stories about her ancestors and the role they played in assisting the Freedom Seekers. The Freedom Seekers were afforded the opportunity to work for pay on the family farms of Keysville residents. They would cut down trees and build houses. Some would stay up all night to keep the foxes from eating the chickens. Some would go on to marry into families of those who provided work and shelter for them. The residents of Keysville also provided a sense of security for the Freedom Seekers. “There was no way to keep people in search of the Freedom Seekers out of the area,” said Jones. “There was nothing more, at the time, than a small narrow dirt road that ran through Keysville. So, there was a network of residents who knew when there was some odd activity, and would signal the Freedom Seekers to take shelter. So much of what I know today came from sitting in that big ol’ swing on the front porch with my distant cousin Miss Katie Harrison.”

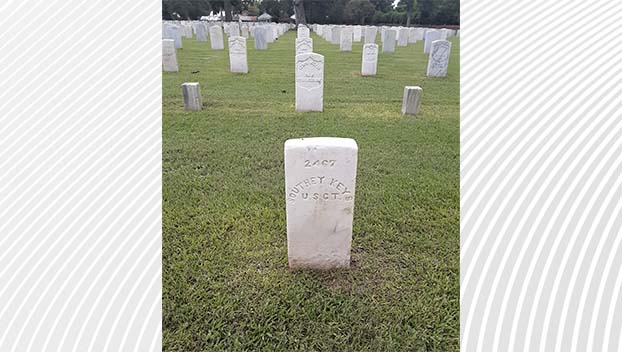

Many of the residents of Keysville fought in the Civil War. A descendent of Southby Keys, who was also Southby Keys, enlisted and served in Company K of the United States Colored Troops in Washington during the war. He died in 1865 of smallpox in Morehead City, North Carolina, and is buried in the New Bern National Cemetery. He was one of many residents from Keysville who enlisted in Company K. Many of whom went on to live out their lives while receiving their military pensions.

Though most of the original homes and structures in Keysville have given way to time, their memories certainly live on and remain a pivotal part of the history. At the corners of Highland and Keysville roads, once stood one of the first pillars of Keysville. The Keysville AME Zion Church was built around 1880. One of those who first attended the church was Willam John Moore, from Blounts Creek. His parents Alfred and Peggy purchased 25 acres of land in Keysville in 1848. Moore would go on to become a noted chaplain and a preacher who organized 68 congregations statewide and build 11 churches. He also became the first financial supporter of the newly founded Livingston College in Salisbury in 1879. Moore was also instrumental, through his financial support, in the founding of the African American newspaper the Start Zion in 1884.

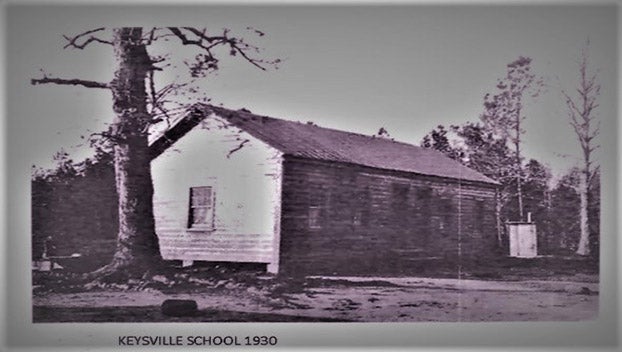

Records indicate a Rosenwald school was built right next to the church in 1927, after the school sanctioned by Beaufort County Commissioners to be a “colored” school burned to the ground. The Rosenwald schools were the vision of Julias Rosenwald, philanthropist and president of Sears and Roebuck and Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute. Hailed as one of the most important initiatives to advance black education, the schools were built specifically for African American children in the south. “This school was one of 813 built in North Carolina,”said Jones. Children of the freedoms seekers were known to have attended the school side-by-side with the other children in Keysville.

Nearby on Highland Drive is Cedar Hill Cemetery. Land for the cemetery was donated by some of the Keys ancestors around 1890, with the intent that it be used as a Black cemetery.

Perhaps the most recognized name to have lived in Keysville is Sarah Keys. Born in 1929, she was the daughter of David and Vivian Keys, who bought land and ran a dairy farm there. Her father is credited with the building of a school and church, specifically for blacks. Keys, who attended a white Catholic Church in Washington reached out to the Sister Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary of Scranton, PA, and asked if they would start a black Catholic church in Keysville and they obliged, and the Mother of Mercy Catholic Church was built, with the help of David Keys and other Black people who lived in Washington. The Mother of Mercy Catholic School on West 9th Street near Market Street in Washington, opened in 1927. It was the first integrated and first accredited high school in Washington.

Born at the height of the Jim Crow era, Sarah Keys went on to serve in the Unites States Womens’ Army Corps. During a bus trip home while on leave, Keys was ordered to the back of the bus because of the color of her skin to make room for a White Marine. Refusing, she was hauled off to jail and stood for 13 hours before her release, so as to not soil her Army dress uniform. Knowing that current laws outlawed segregation on interstate highway travel, she went on to file a case with the Interstate Commerce Commission, which ruled against her. She would not take no for an answer and eventually the Commission ruled in her favor that “neither interstate buses, nor trains could assign seating based on the color of a passengers’ skin.” That 1955 ruling came just two weeks before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. “Sarah Keys is a third cousin to me,” said Jones. “She literally changed the content of history. I can now sit on a bus, or a plane, or anywhere I want, thanks to her.”

Keys, who now resides in Brooklyn, New York, will turn 96 this year. “She remains as sharp as a tack and still vividly remembers the stories of her elders who helped the Freedom Seekers find caves for safe keeping or would find them shelters to live in,” said Jones. “Her remembrances have been invaluable to me when telling the stories of the Underground Railroad.

A street in Keysville has been named in her honor.