The legacy of Susan Dimock lives on today

Published 4:00 pm Friday, March 17, 2023

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Clark Curtis for the Washington Daily News

Editors Note: During Women’s History Month, Clark Curtis will be taking a look at some of the women, past and present, whose stories and lives have contributed in some way to the deep and rich history of Washington.

The words prodigy and pioneer are often used by historians when speaking of Washington, North Carolina native Susan Dimock. Born in 1847 to Henry and Mary Malvina Owens Dimock, she never received a high school diploma or a college degree. However, what she was able to accomplish in a life that was tragically taken away at the age of 28, was quite incredible. Without hesitation and with total commitment, she crossed the threshold of the male dominated world of medicine and became an internationally renown doctor and surgeon, creating a legacy which has empowered women for generations to come.

It was the death of Dimock in 1875 while aboard the steamship SS Schiller which ran aground in fog off England’s Scilly Isles that caught the attention of historian and author Susan Wilson. At the time Wilson was a freelance writer for the Boston Globe writing history columns. She came across a series of articles from 1875 about the death of Dimock and was taken aback by all of the outpouring of public concern and hope that she might still be alive. “It was fascinating to read the articles about such a strong woman, and how revered she was in Boston,” said Wilson. “I felt the need to find out more about her as it would make a great story. When I learned some years later that no one had written a book about her, I said to myself, “If not me than who?””

As Wilson shares in her soon be be released book, “Women and Children First: The Remarkable Journey of Dr. Susan Dimock,” Dimock from a very early age knew that she wanted to be a doctor. Though her mother was a bit dubious, she received full support from her father. This at a time when women were expected to stay home and do the cleaning, cooking and, childcare. Men were expected to be breadwinners. “Dimock,” said Wilson, “would have no part of that.”

Dimock would often be found spending many an hour with local family physician, Dr. Solomon Satchwell and would often accompany him on his rounds out in the country. She also had a fascination with Latin. Thanks, to her principal at the Washington Academy school, Gilbert Bogart, she became quite proficient in Latin. This allowed her to read the medical books that Dr. Satchwell would share with her, which were written in Latin “At the age of 11, Dimock was on a beach trip with some friends,” said Wilson. “One of her friends developed a tooth ache and she remembered one of her aunts telling her about a specific root that would ease the pain. She found the root, rubbed it on her friends tooth, and spent the night with her to make sure she was okay. She was already being a doctor!”

Growing up, Dimock lived with her parents at the historic Lafayette Hotel, which they owned and operated in downtown Washington. In 1864 at the height of the Civil War, the hotel burned to the ground. Dimock and her mother, her father then deceased, would move to Boston. While in Boston, a friend of Dimock’s, who could see her passion for medicine connected her with the founder of the New England Hospital for Women and Children, Dr. Marię Zakrzewska. She immediately took her under her wing and Dimock soon became an informal intern. “Everyone thought she was an exceptional student and encouraged her to apply to Harvard Medical School. However, she was rejected on more than one occasion because of gender. This was in 1867 and Harvard did not begin accepting women until 1945. Had she lived to be 98 she too would have been accepted.”

Dimock learned of other medical schools in Europe. And, with the help of others, including her mother, collected money and applied to the University of Zurich. “At the time the university was doing an experiment and accepted Dimock and six other women from around the globe,” said Wilson. “They became known as the Zurich Seven. They were allowed to work side-by-side with the men in the med school. And to no surprise, Dimock excelled in her work.”

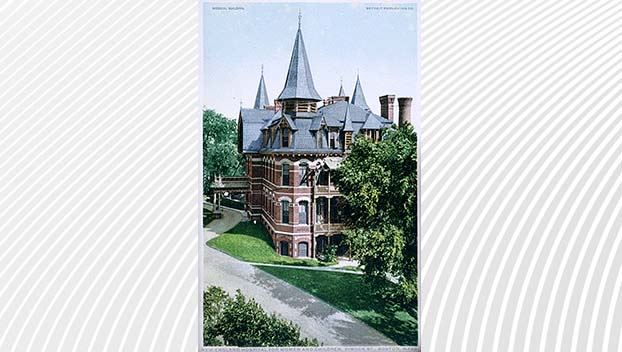

Upon her return in 1872, Dimock became a resident physician at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. “At the time she probably was the most skilled female surgeon in the United States,” said Wilson, “She handled the most important surgeries at the hospital. In addition she was in charge of the first professional nursing school, the first of its kind in the U.S. She would hand out the diploma to the first trained professional nurse in the country. There were no other established schools before then, where students were offered on the job training and allowed to hang out with other nurses.”

And because Dimock wanted to make more money to pay off her college debts, she opened up a private practice in downtown Boston. “After six or seven hours at the hospital, she would go straight to her private practice,” said Wilson. “And within two-and-a-half years, she had all of her college loans paid off.”

Unfortunately, she died just three years later in 1875. However, as Wilson points out, the legacy that she left behind as a pioneer in the field of medicine would live on. “Most, at the time of her death, including the Dr. Zakrzewska and other prestigious women physicians, said it was going to be a long time before anyone with her remarkable and unusual skill set as a surgeon would be able to replace her,” said Wilson. “Fortunately, at the time she was such an inspiration to many women and that within a decade, more and more women were taking up surgery and becoming great surgeons. Today, more than 50 percent of all medical students are women.”

Wilson said people need to remember that when Dimock returned from Europe there were only an estimated 300 female doctors in the U.S. as compared to 55,000 men. And that she was one of a very small group that had to continually fight for who they were and to be taken seriously. A lot of people at the time, both men and women, felt it was too manly for any woman who tried to have a professional career, let alone in medicine. “But at 5 feet, 4 inches she broke the mold,” said Wilson. “She was such a lovely, charming and a gentle soul, which threw everyone off as to how the stereotypical doctor should act and look. One doctor described her as having Southern charm with Yankee grit. A patient once commented that she “ruled the hospital like a Napoleon.” And Wilson added, “she managed to pull it off so beautifully but with great strength at the same time.”

Dimock never backed down from her desire to be accepted into the medical establishment. She tried countless times to become a member of the American Medical Association (AMA) and the Massachusetts Medial Society (MMS), only to be rejected. However, she did become the first female to be admitted to the North Carolina Medical Society (NCMS) as an honorary member, even though she didn’t work or live in North Carolina. One of the officers of the NCMS was her old friend and mentor, Dr. Satchwell. It wasn’t until seven years after her death that a woman was finally accepted in the MMS. “If there is someone as good as her, then she should be allowed in,” one male doctor was quoted as saying.

Nine years after her death, the street where the New England Hospital for Women and Children resided was renamed Dimock Street. “If this isn’t an example of a female role model, I don’t know what is,” said Wilson. “She broke the preverbal glass ceiling for others.”

“Dr. Dimock became a true leader, a standard bearer and pioneer for women entering the field of medicine as well as fighting for the rights of women inclusions into all male medical associations,” added Leesa Jones, director of the Washington Waterfront Underground Railroad. “Her legacy of courage can inspire all to kick open the doors of anything that acts as an obstacle to their destiny. Her journey, ‘a true profile in courage’ shows us how to do just that.”