Awareness comes in the form of miracle baby

Published 8:49 pm Monday, January 26, 2015

VAIL STEWART RUMLEY | DAILY NEWS

MIRACLE GIRL: Sarai Topping, at seven months, is a normal little girl, with few medical issues. At birth, however, Sarai suffered from omphalocele, in which organs are located in a sac outside of the body.

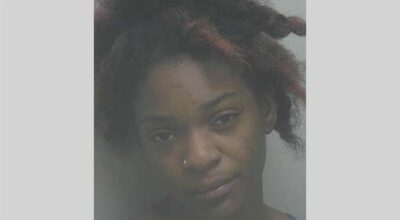

Saturday is National Omphalocele Awareness Day. Those who have never seen, nor heard, the word omphalocele are not alone, and one local mom wants to change that.

“Not many people talk about it, or know about it,” said Washington resident Jewel Topping. “I didn’t know anything about it.”

Topping was 17 weeks pregnant with her little girl Sarai when she went in for a regular checkup with her doctor.

“When I went to find out the sex of the baby, the technician got up and kind of ran out of the room and brought the doctor in,” Topping said.

The doctor told her Sarai had an omphalocele — a birth defect that’s related to a hernia, but in cases of omphalocele, a baby’s intestines and/or other internal organs develop outside the abdominal wall in a thin sac. The condition is often associated with other birth defects, including heart defects and Down’s Syndrome. Surgery on the infant is required if not immediately after birth, then in the months to come.

According to Topping, it was made clear to her that infants born with omphalocele can have a host of medical problems — quality of life for the child was an issue — and brought up the subject of early termination.

Topping said no.

“I felt like if she lived one day or two days or 100 years, who am I to decide?” Topping asked.

She and her husband, Shaquan, a U.S. Navy yeomen stationed on a submarine in Charleston, struggled with what that meant for their family.

“He was stunned and terrified and didn’t know what to do,” Topping said. “He just kept trying to figure out why and what caused it when there isn’t a cause.”

JEWEL TOPPING | CONTRIBUTED

HOSPITAL STAY: Sarai Topping stayed in the hospital for seven weeks. As pictured, she spends her days wrapped in an Ace bandage to help her body adjust to organs that were surgically repaired to her body.

The next several months involved countless doctors’ appointments at East Carolina University’s Brody School of Medicine. Topping went into labor twice: once at seven months and again three days before her schedule C-section, but labor was stopped both times because it wasn’t just Topping who needed to be prepared for Sarai’s birth, but two teams of medical professionals, as well: one for the C-section; another for the surgery that would happen immediately after birth.

On June 4, Sarai was born in Greenville. Her mother got to touch her baby once before Sarai was whisked off to surgery.

What followed was a ton of prayers and procedures: Sarai’s intestines, stomach and liver were put back into place; a skin graft made. A second surgery would tighten that further, but it would come undone, and a third procedure did not have the intended effect: Sarai’s lung collapsed; second hole was found in her heart; she caught a staph infection in a kidney.

Fro seven weeks, Sarai was in the hospital, sedated on morphine, her mother unable to even do so much as hold her.

But had she to do it over again, Topping wouldn’t change a thing, because Sarai got better: her infection cleared up, the hole in heart closed — an occurrence the cardiologist didn’t expect to happen, Topping said.

“She’s fine,” Topping said. “She’s propped herself up, can just about crawl. She stands. She does anything the average baby does.”

Every day, Topping wraps an Ace bandage around her baby’s abdomen to keep pressure on the intestines until Sarai can have one more surgery to knit together the muscles of the abdomen that have not developed. During the surgery, Sarai will also have a belly button made for her — a cosmetic procedure. She didn’t have one because in utero, the umbilical cord was attached to the omphalocele, Topping said.

With January named National Birth Defect Month and Jan. 31, National Omphalocele Awareness Day, Topping said it was important for people to be aware of the issue.

While only one out of 5,000 babies born in the U.S. each year is born with an omphalocele, the risk of additional birth defects is heightened — but not in every case, as illustrated by Sarai.

“There’s a whole community out there. It’s not narrowed down to race or a certain location. And the more new mothers I talk to, the more I hear that early termination was the first option (offered). … That should not be the first choice. She’s an example of how good things can be,” Topping said. “I can’t imagine not having her, knowing that she could have had a chance.”