EPA reduces federal protections for waterways

Published 6:55 pm Sunday, February 17, 2019

- NUTRIEN: This 2,000-acre wetland mitigation project near Aurora was completed by Nutrien in the mid-1990s. Changes proposed to the federal Clean Water Act could endanger local wetlands and streams, leading to greater runoff, more polluted waters and greater chance of flooding. (Nutrien)

The EPA’s revised definition for “waters of the United States” could mean trouble for local waterways.

Thursday, the agency released changes to the 2015 Clean Water Rule, an Obama-era clarification of federally protected waters. The revision was made at the instruction of President Donald Trump, who, in 2017, signed an executive order directing the EPA and the Army Corps of Engineers to rescind or revise the definition of WOTUS.

According to the EPA, the revision is designed to “protect the nation’s navigable waters, help sustain economic growth and reduce barriers to business development.” In the process, the agency said, the new rule makes it easier to understand which waters are protected — an understanding that will save landowners time and money when it comes to federal permits — and hands jurisdiction of some waterbodies back over for states’ management.

But the result has environmental advocates concerned about the future health of the region’s streams, wetlands and rivers.

Under the new rule, intermittent streams, ditches and wetlands not adjacent to another protected waterbody will no longer fall under federal clean-water regulations, leaving it up to the states’ regulations. However, for states like North Carolina, where the General Assembly has prohibited any state environmental protections greater than minimum federal standards, that could leave an estimated 49,000 miles of streams unprotected from polluters and development, according to Geoff Gisler, senior attorney with the Southern Environmental Law Center.

“That’s probably underestimating the effect, because that doesn’t include the data from the smallest streams,” Gisler said. “The EPA, in their document, says that North Carolina has about 4 million, 300 acres of wetlands. We think most of those would be in danger, particularly in the coastal plain. It would be an immediate impact in Washington, and downstream effects would be from Durham, east. … The collective loss of protections would be a major loss for y’all.”

For Heather Deck, executive director of Sound Rivers, what stands to be most affected as a result of the revisions hits very close to home: pollution and flooding. If streambeds that become actual streams after rainfall are paved over indiscriminately, or wetlands filled in, the chances increase for more, and greater, flooding than Beaufort County has already seen in recent years.

“Right now, you can’t pave over them, you can’t discharge anything into them — this is the bedrock of our clean water protections we’ve had for 50 years,” Deck said. “These wetlands play a vital role in filtering our pollution, but they also help protect life, limb and property, and with climate change, we know these flooding events are going to become more frequent. … What they’re rolling out here is not backed up in science, and will increase flooding.”

Another effect of more impervious surfaces, such as parking lots and roads, is greater run-off and more pollutants into larger waterways, according to Gisler.

“I think what people would see is that, one effect would be a lot of these streams and wetlands that are really good at filtering water would just be filled in. People would notice downstream, there’s more sediment. People would notice that the fishing isn’t as good at places they like to fish,” Gisler said. “I think people would see the effects pretty soon.”

The reclassification of small streams and wetlands on the federal level does not automatically mean they’ll have no protections in the state. North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality will have to review the changes and legislation must be created to either add protections to the no-longer federally protected waters or comply with the federal government’s definition. If protections are added on the state level, the problem then becomes about resources.

“The more immediate effect would be the state doesn’t have the resources to take over the program the Army Corps of Engineers runs. They’re already overstaffed and overburdened,” Gisler said. “To expect them to take on the tasks that the Corps has now is just not realistic.”

Gisler said the SELC has engaged ecologists and economic analysts to help understand exactly how much of an impact the clean water rule revisions might have and is partnering with agencies like Sound Rivers to get information out to the public.

“There a lot of rules that get amended, that get changed and things change from administration to administration, but this is something that goes far beyond anything that has happened in several decades,” Gisler said. “The really important issue, that we’re working hard to get the information out there, is that this an important issue that will affect people’s lives.”

With the release of the proposed WOTUS definitions, the EPA will take the public’s comments for the next 60 days. The public comment period will close April 15. Public hearings will also be held in Kansas City, Kansas, Feb. 27 and 28.

Sound Rivers has launched a campaign to impel Gov. Roy Cooper to take a stance on the issue and to encourage residents to participate in the public comment period, Deck said.

“I think, for us in coastal Carolina, our waterways are a regular part of our lives. We certainly want to make people aware this is a step in the wrong direction, and there’s an opportunity for the people to speak up,” Deck said. “We all depend on clean water. We can’t live without clean water — we can’t have a good economy without it either.”

Public comments can be submitted to the EPA through www.regulations.gov, by email OW-Docket@epa.gov, and by mail at U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, EPA Docket Center, Office of Water Docket, Mail Code 28221T, 1200 Pennsylvania Ave. NW, Washington, DC 20460.

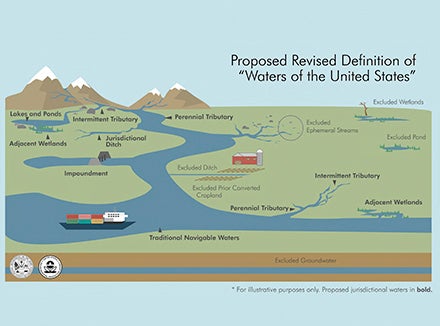

PROPOSALS: This infographic from the EPA shows which waters would be considered federally regulated waters and which would be excluded from the federal government’s oversight.

WATERS EXCLUDED FROM “Waters of the United States” PROTECTION

- Ephemeral features that contain water only during or in response to rainfall.

- Groundwater.

- Ditches that do not meet the proposed conditions necessary to be considered jurisdictional, including most farm and roadside ditches.

- Prior converted cropland. This longstanding exclusion for certain agricultural areas would be continued under the proposal, and the agencies are clarifying that this exclusion would cease to apply when cropland is abandoned (i.e., not used for, or in support of, agricultural purposes in the preceding five years) and has reverted to wetlands.

- Stormwater control features excavated or constructed in upland to convey, treat, infiltrate, or store stormwater run-off.

- Wastewater recycling structures such as detention, retention and infiltration basins and ponds, and groundwater recharge basins would be excluded where they are constructed in upland.